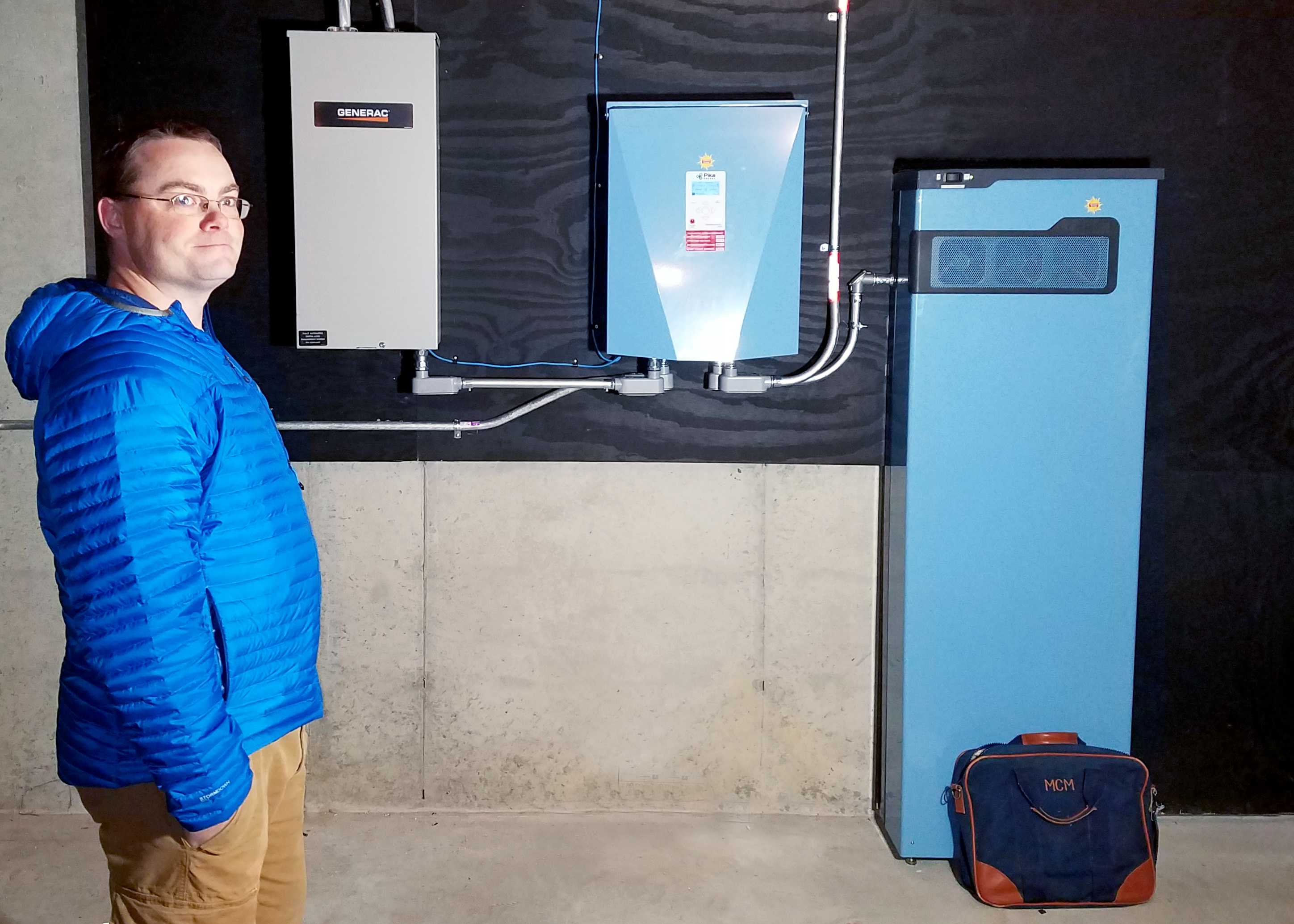

Matt & Carrie Thomas’ home in Bowdoin has two solar arrays with the ability to put out about 10 kilowatts of electricity. He drives a Chevy Volt and uses wood and electric heat pumps to heat the home. Photo: ReVision Energy

A window into the not-so-distant future

By Darren Fishell

Matthew Thomas admits his and his wife, Carrie’s, home in Bowdoin is a little ahead of its time.

“Since I was a kid I’ve always wanted to have solar panels,” Thomas says. “I’m a big tech guy and was really into Star Trek, and I wanted to have that kind of futuristic, my- own-spaceship kind of thing.”

What makes the system particularly forward-looking is 15 kWh of battery storage that enables him to store the electricity his solar panels produce when the sun is out, to be used at a time when it’s not or when power from the grid is not available. In October, his battery system enabled him to ride out the worst power outage in Maine’s history in comfort—without burning any oil. He gave his diesel generator to a relative and sent his other generator equipment to a neighbor.

Thomas’s battery-tied solar system is on the leading edge of renewable energy home generation, motivated by a fondness for sustainability, self-sufficiency and technology. At a payback period of around 12 years and cost of about $30,000 after rebates and tax credits, it takes that kind of commitment to make the case for such a system.

But experts say that could change as utilities and policymakers begin to find ways to harness power from battery storage systems and create incentives for their adoption.

Batteries don’t pay everywhere

Prices for solar panels have been coming down for decades, and systems like Thomas’s show battery storage technology is ready for deployment. But the cost of equipment is not the part of the equation that needs to change to make battery storage commonplace, according to Hans Albee, solar energy system designer at ReVision Energy’s Liberty office.

Albee says that for customers to make a purely economic case for installing a battery-tied solar system, how those homeowners are compensated for the electricity they send back to the grid is more important than further reductions in equipment costs.

In markets offering residential customers power at rates that change throughout the day—to shift use to times of low demand—battery storage can increase the value of solar power by making the electricity generated by solar available when the sun isn’t shining or when the price of electricity is higher.

That’s not the case in Maine, where small electricity generators like Thomas get the same credits on their power bill no matter how or when he puts power back on the grid, a system called net metering. That leaves no incentive for a customer with solar panels to store power for later use.

For now, Thomas says his battery system primarily acts as an alternative to a diesel generator, which for him has many benefits. He says he’s not worried about fuel costs, or a road being impassable for a fuel delivery, or about mechanical failures.

“If you compare going with this battery to a standby backup generator, your costs are essentially the same but you have zero maintenance,” Thomas says.

Solar-saturated markets need battery storage

Matt Thomas has eliminated all fossil fuel-fired heating in his home, relying on an array of electric Stihl yard equipment to cut wood for heat.

Incentives for dynamic, real-time pricing of electricity from small generators are only beginning in New England, starting in Massachusetts, which leads the region by far for solar capacity. But it’s far from Hawaii or California, where an abundance of solar generation has come online, requiring new approaches and new technology to handle large amounts of power fluctuating with the weather.

The California Solar Energy Industries Association in early February made clear its sense of where the market is heading by changing its name to the California Solar and Storage Association.

In Hawaii, where the cost of imported oil makes electricity the most expensive in the country, the state’s largest utility redirected incentives to focus on solar systems that are paired with battery backup.

“A battery is a necessity now if you want to install in Hawaii,” says Geoff Sparrow, director of engineering for ReVision Energy.

Subsidiaries of Hawaiian Electric Industries phased out incentives for standalone solar panels and in early February received approval for new incentives that target storage.

One program allows customers to get credits only for power put back on the grid before 9 a.m. or after 4 p.m. and another allows the utility to control home battery systems as a grid resource, a technology- enabled meshing of the traditional grid and smaller generators generally referred to as a “smart grid.”

That kind of battery backup will play a big role in the state as it leans heavily on an abundant solar resource to meet a goal of having 100 percent renewable power by 2045.

Homegrown high tech

Those markets have created an opening for companies like Pika Energy in Westbrook, which says its technology for integrating small, distributed power generators into the grid is ready to meet the demand.

Pika makes a range of smart solar appliances that enable homeowners to capture, store and use more clean energy in their

homes. Its systems manage the flow of electricity between multiple sources, including the power grid, generators like solar panels, and battery storage. Their battery product competes with the likes of Tesla’s Powerwall, which is perhaps the most recognized home storage product.

Thomas says he considered the Powerwall but prefers Pika’s technology for the ability to put solar panel power directly into the battery, without losses that come with converting that power from direct to alternating current.

Tesla’s battery advertises an ability to put out 90 percent of the power it takes to charge its Powerwall—a measure called “round-trip efficiency”— and Pika’s system advertises greater than 90 percent efficiency, boosted when avoiding conversion for incoming power.

Pika released its battery system last year, using Panasonic technology, which it packages with its inverters in what it calls its “Energy Island” product.

Thomas was a first adopter of Pika’s higher-capacity Energy Island, which connects straight into to the critical load panel for his home and puts out enough power to keep all his major appliances running, charge his Chevy Volt and power an array of electric Stihl yard appliances, including the chainsaw he uses to cut wood for the wood stove. The stove is backed up by electric heat pumps, most often powered by his solar array.

Thomas says he’s had no problems with the system since the installation.

Maine is far from solar saturation

Matt Thomas’ home uses a Pika Energy island to manage his power use and provide roughly 15 kilowatt-hours of electricity backup.

Until more solar power comes online in New England, Albee and Sparrow say it’s not likely there will be pressure to implement real-time pricing to shift solar generation to another time of day, though the metering technology is available.

There’s still relatively little solar power in New England, and the peak production of those systems aligns well with the region’s peak demand, on the hottest days of summer.

Albee and Sparrow say solar capacity must make up about 15 to 20 percent of peak load on the grid before utilities feel the pressure to encourage storing that energy to use when the sun isn’t shining.

In Maine, that kind of pressure is still a way off.

While the number of customers in Maine putting power back onto the grid grew more than 25 percent last year—for a second year in a row—these small-scale solar outputs were, at their peak in August, still roughly one percent of the total power generated, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Big solar projects due to come online in Maine and elsewhere, driven recently by a clean energy procurement by a group of southern New England states, could increase that total significantly. That procurement alone would support adding 130 megawatts of capacity to the grid in Maine, or about 3.6 times the capacity of all small-scale solar systems online in Maine last year.

And there are still other grid-scale solar projects coming online in other parts of the state, with a pilot project in Pittsfield, one from the municipally-owned Madison Electric Works that came online in October and another planned by Kennebunk Power and Light for late 2018.

Across New England, solar capacity is projected to double from 2017 to 2026, which the regional grid operator says they can manage primarily with fast-start natural gas power plants. But they, too, have given a nod to the role batteries might play, “as they become larger and more cost-effective,” the ISO states on its website.

“The feeling in the industry is that where we are with batteries today is where solar PV was 10 years ago,” says Jeremy Niles, marketing manager of Pika. “It has that same sort of growth potential, it has that same sort of energy around it.”

This article was re-printed from the Spring/Summer 2018 issue of Green & Healthy Maine HOMES. Subscribe today!